|

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

Feature Articles: Olympic and Paralympic Games Tokyo 2020 and NTT R&D—Technologies for Viewing Tokyo 2020 Games Vol. 19, No. 12, pp. 69–77, Dec. 2021. https://doi.org/10.53829/ntr202112fa9 Badminton × Ultra-realistic Communication Technology Kirari!AbstractNTT provided technical support through Kirari!, an ultra-realistic communication technology, for the TOKYO 2020 Future Sports Viewing Project spearheaded by the Tokyo Organising Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games. This article presents results of demonstrations of a next-generation immersive technology for providing a sense of “being there,” namely through the sense of presence and sense of unity, by transmitting holographic images of the badminton matches held at Musashino Forest Sport Plaza to a remote location (National Museum of Emerging Science and Innovation (Miraikan)). Keywords: sports viewing, highly realistic experience, holographic video transmission 1. Overview of the TOKYO 2020 Future Sports Viewing ProjectThe beauty of watching performances live is being able to experience the sense of presence and sense of unity that can be felt when you are actually at the venue. In other words, it enables experiencing the sensation of having athletes or artists being right in front of you and sharing the same space with them when watching sports events or live concerts, rather than viewing them as images on a flat screen. Despite dramatic improvements in screen size, image quality, and resolution, online streaming and live viewing still can transmit only flat-screen images. It is therefore not possible to fully convey a sense of presence, such as the athlete’s in-the-moment excitement, strength and beauty of the physical form, and sense of unity between the athletes and audience. For the TOKYO 2020 Future Sports Viewing Project spearheaded by the Tokyo Organising Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games, we carried out technology demonstrations aimed at delivering the experience of being at the badminton venue of the Tokyo 2020 Games to those who could not attend the actual event by using Kirari! ultra-realistic communication technology to transmit holographic images of the event (Fig. 1).

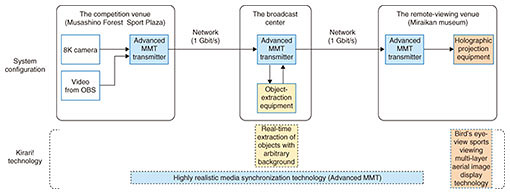

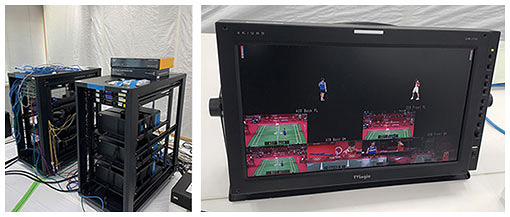

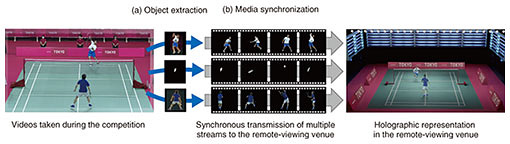

We initially planned demonstrations of live viewing by inviting the general public. However, to prevent the spread of the novel coronavirus, we cancelled the public demonstration and instead opened “The Future of Sports Viewing—Next-generation Immersive Technology Demonstration Program” at the National Museum of Emerging Science and Innovation (Miraikan) for the media from July 30 to 31, 2021. 2. System configurationFigure 2 shows the overall system configuration for the technology demonstrations. We set up 8K cameras (Fig. 3) at the Musashino Forest Sport Plaza, the venue for the Tokyo 2020 Games badminton competitions, and transmitted video images taken during the badminton matches via a 1-Gbit/s network to the broadcast center. We then used the real-time extraction of objects with arbitrary background, a component technology of Kirari!, to selectively extract only the images of players and shuttlecocks from the transmitted 8K images at the broadcast center (Fig. 4). Using highly realistic media synchronization technology (Advanced MMT (MPEG Media Transport)) [1], we then synchronously transmitted the extracted images along with multiple images that included video and audio provided by the Olympic Broadcasting Services (OBS) to the remotely located Miraikan museum.

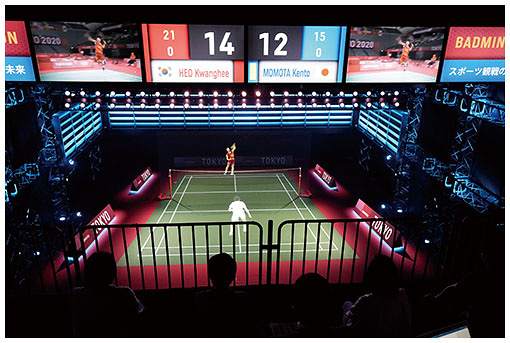

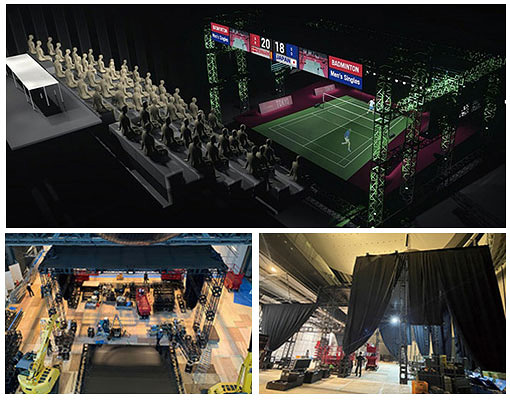

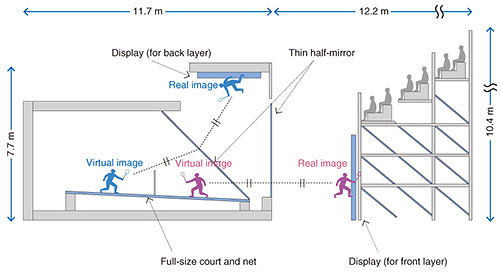

We set up an approximately 100-seater spectator stand and a full-size court equipped with holographic projection equipment at the remote-viewing venue to recreate the actual venue (Fig. 5). The extracted images of players and shuttlecocks were holographically displayed by presenting players in their actual positions in front and behind the net using the bird’s eye-view sports viewing multi-layer aerial image display technology. As a result, we were able to create a space where the badminton players appeared to be actually present in the remote-viewing venue.

3. Kirari! technologies3.1 Real-time extraction of objects with arbitrary backgroundThe real-time extraction of objects with arbitrary background is a technology for selectively extracting only the specific objects in images, such as players and shuttlecocks, from the videos taken during a competition [2] (Fig. 6(a)).

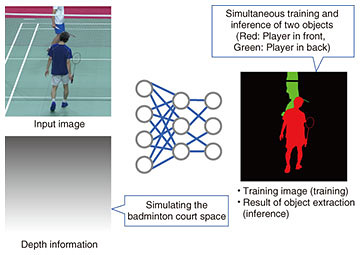

Normally, extraction of only the objects from videos requires using a green or blue background and erasing the background color by chroma keying. This technology, however, enables extracting only the objects from the raw images of the competition venue in real time without the need for any special background environment. To apply this technology to the badminton matches, we carried out the following five improvements on our previous system [1] that is for less complicated content. (1) Individual extraction of each player in the front and back sides of the court Separately extracting the front and back players is not possible with the conventional technology. To achieve this, we developed a deep learning model that can simultaneously extract and infer front and back players by inputting depth information simulating the badminton court space. This enabled the extraction of individual players for a game like badminton where players are located separately in the front and back sides of the court. We therefore succeeded in stable and accurate extraction of objects (Fig. 7).

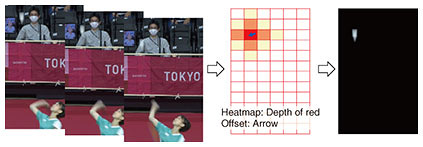

(2) Improvement of output-image resolution and frame rate of players’ images The conventional technology only supports resolutions of up to 4K and frame rates of up to 30 fps. The maximum resolution of player images that can be achieved using 4K cameras is only approximately 640 pixels; and the roughness of aerial images becomes evident when they are magnified and projected into life-size images. A frame rate of 30 fps does not allow tracking of rapid movements such as when the player is smashing a shuttlecock, leading to disrupted images. We therefore carried out multi-layering of the image frames to be processed and leveling of computing resources to support images from 8K, 60-fps cameras. As a result, we were able to produce smooth, high-definition images of players at 930-pixel resolution and 60-fps frame rate. (3) Stable extraction of subtle and rapid shuttlecock movements Since shuttlecocks are very small and move very rapidly in the video, using conventional image-recognition methods results in considerable noise and flickering and in discontinuity and incompleteness of the shuttlecock trajectory. We therefore developed extraction algorithms specific for the shuttlecock and succeeded in detecting its exact position and in accurately extracting its various contours. To detect shuttlecock position, we devised a method for learning the shuttlecock’s position and movement information by inputting continuous frames in a convolutional neural network (CNN) to eliminate the effects of small objects similar to the shuttlecock appearing in the video (such as seat guide lights). The position of the shuttlecock was determined on the basis of the rough position (heatmap) and correction value (offset) obtained from the CNN (Fig. 8). Extraction of the shuttlecock image was carried out by generating the image using a background-subtraction method and filtering with the extracted shuttlecock position and shape and predicted shuttlecock information (position, contour, and motion blur level) in the next frame. This resulted in a precision of 90.7% and recall of 90.3%, levels that can be used for realistic sports viewing.

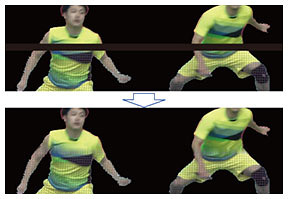

(4) Automatic correction of missing parts in player images As shown in Fig. 9, when the player at the back of the court overlapped with the net, a black gap zone appeared on the player image. Images were corrected by inferring the missing parts on the basis of the color information above and below the gap zone.

(5) Automatic generation of player’s shadow Reproducing the players’ shadows appearing in the actual venue and in the remote-viewing venue enables the creation of more natural player images. We extracted the shadows from the video based on the results of player-image extraction. We carried out this step quickly by determining the range where the shadows might appear on the basis of the height of the player’s jump and lighting conditions of the competition venue. 3.2 Highly realistic media synchronization technologyThe highly realistic media synchronization technology (Advanced MMT) is NTT’s proprietary technology developed by extending the media transmission standard MMT and enables the transmitting of various continuous data (streams), such as video, audio, and lighting information, while maintaining their time synchronization. For this project, we synchronously transmitted multiple streams, such as video of the competition taken at the venue, audio, images of players extracted from competition videos, extracted shuttlecock images, video obtained from OBS, etc. and displayed the necessary data on the remote-viewing venue at the appropriate timing to create a highly realistic spatial representation (Fig. 6(b)). 3.3 Bird’s eye-view sports viewing multi-layer aerial image display technologyTo deliver the experience of watching as if viewers were at the competition venue, we created a space that physically simulated the actual venue (Fig. 10). We set up a full-size court and net, as well as a spectator stand with the same downward viewing angle as in the actual venue. We used the bird’s eye-view sports viewing multi-layer aerial image display technology for projecting the holographic representation of players at the same position within that recreated space.

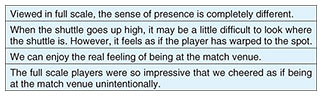

With the conventional holographic projection method called Pepper’s ghost, aerial images are displayed by reflecting images on the display to a half mirror tilted at a 45-degree angle. Only a single layer of an aerial image can be displayed. Single-layer display, however, cannot be used to display players in front and behind the net, as in badminton, in different locations (layers) in the projected space. With our technology, a spectator stand at the same height as the actual competition venue was set up, and the locations of the court, net, two half-mirrors, light-emitting diode displays, and the projectors were optimized to create a realistic appearance of the players in front and behind the net. This enabled the holographically displaying of the two players at their correct positions. The use of two half-mirrors, however, results in a discontinuous appearance of the shuttlecock, which moves back and forth between the two mirrors. Since this problem is a structural issue arising from having two physically separated layers, there is no perfect solution to it. To produce a more natural appearance, we repeatedly conducted trial-and-error experiments on the timing for switching the shuttlecock’s display layers and came to the conclusion that the best timing for switching is when the player hits the shuttlecock. To determine the best timing for switching, we combined multiple approaches, such as determining the shuttlecock position through analysis of lateral court images, determining the timing when the shuttlecock is hit through detection of hitting sounds from the audio during the match, and human operators watching the game manually switching the display layers. The combination of multiple approaches enabled the real-time switching of shuttlecock-image display positions. 4. Results of demonstrationsThe technology demonstrations were conducted for four days from July 30 to August 2 during the badminton tournament finals. Press representatives participated in the viewing demonstrations for not only the recorded videos of the preliminary rounds but also for the live coverage of the men’s doubles, women’s singles, and men’s singles events. Many participants commented that they were able to gain a highly realistic experience of the matches (Table 1).

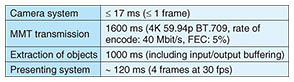

The highly realistic environment with a full-size court and net and life-size holographic projections of players apparently elicited a sensory illusion that the players were actually in front of the participants. This indicates the possibility of achieving an emotional connection at a deeper level than when watching on television. The spectators were able to more easily feel the energy and vibe during the competitions or the excitement of players before the start of the matches, and even the emotions associated with winning or losing. When Kento Momota fell to his knees when he lost in the second round of his match during the group play stage, the realistic sense of his presence in the remote-viewing venue was very striking. In terms of object-extraction performance, we succeeded in real-time processing of 8K, 60-fps videos. There are issues that need to be addressed for extraction accuracy such as when images of the two players overlap or extraction for doubles matches. Nevertheless, we succeeded in processing the images without missing parts or errors that could hinder proper viewing of the games, even for players wearing different uniforms for all the six live broadcast experiments. We also confirmed that there were no errors in the correction of the black zones caused by the net and in the addition of shadows. For the shuttlecock images, however, more improvements are necessary due to considerable discontinuity depending on the viewing position. In terms of transmission performance, the total end-to-end delay from the competition venue to the remote-viewing venue was less than 2800 ms. Table 2 lists the lag time details. The MMT transmission delay included network transmission delays of approximately 1 ms between the competition venue and broadcast center and approximately 0.1 ms between the broadcast center and remote-viewing venue. Delays in object-extraction processing included buffering that takes fluctuations in processing time, etc., into consideration, but the actual delay in extraction processing excluding the buffering was less than 400 ms.

Since the demonstrations involved one-way transmission of images from the competition venue to the remote-viewing venue, an approximately 3-s delay did not cause major problems. However, our future goal is to connect the two venues bi-directionally and deliver the cheers from the audience in the remote-viewing venue back to the competition venue, in which case, significant lag times would become problematic, making it necessary to further reduce processing time. We were able to confirm that the above performance of the demonstration system were sufficient in delivering a realistic experience of the presence of the athletes in the remote-viewing venue. 5. SummaryAs part of the TOKYO 2020 Future Sports Viewing Project, we applied Kirari! to badminton matches and demonstrated that it can be used to deliver a realistic experience of being at the competition venue. Although there are issues regarding accuracy of extracting player images and in the method for displaying the shuttlecock, we succeeded in demonstrating the possibility of a new sports-viewing experience, beyond what television can provide, for the Olympic Games, an event that attracts attention from all over the world. Going forward, we will carry out improvements in extraction performance and other technical aspects, as well as deploy the technology to other games and areas, such as for music concerts. We will also study methods of minimizing lag time for bi-directional connection between competition and remote-viewing venues and conduct research and development on Kirari! and other technologies for achieving the Remote World and eventually make future proposals that will surprise the world using communication technologies. AcknowledgmentsWe would like to thank the members of the Innovation Promotion Office of the Tokyo Organising Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games for helping us resolve various issues in conducting this technology demonstration, representatives of the Miraikan museum for organizing and leading the project, and representatives of partner companies for their technical support. NTT is an Olympic and Paralympic Games Tokyo 2020 Gold Partner (Telecommunication Services). References

|

|||||