|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

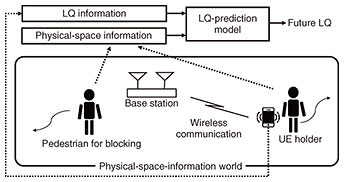

Regular Articles Vol. 23, No. 3, pp. 42–48, Mar. 2025. https://doi.org/10.53829/ntr202503ra1 5G Throughput-prediction Technology for 28-GHz Channels Using Physical-space InformationAbstractAdvances in wireless communications, such as the 5th-generation mobile communication system (5G), have enabled a wide variety of devices to be connected to wireless networks. In 6G, all physical entities will be connected to wireless networks, and their physical-space information, such as position and velocity, will be available for new mobile services. NTT’s Innovative Optical and Wireless Network (IOWN) will accelerate to obtain the physical-space information from various sensors. Therefore, mobile traffic is growing rapidly toward 6G. The use of the millimeter-wave (mmWave) bands is promising to increase the capacity of mobile networks. However, the mmWave link quality (LQ) is strongly affected by surrounding objects. To stably use mmWave bands, an effective solution is to predict future LQ and adaptively control wireless communication. This article introduces 5G throughput-prediction technology that is based on deep neural networks using physical-space information and an automated 5G measurement environment using humanoid robots for deep-learning evaluations. Keywords: millimeter wave, physical-space information, throughput prediction 1. Background and overviewAdvanced wireless communication systems enable a wide variety of devices connect to wireless networks. The 5th-generation mobile communication system (5G) contributes to creating a wide range of innovative applications, such as virtual and augmented reality (VR/AR), as well as services in diverse industries that require high speed, low latency, and high reliability [1]. In 6G, all elements, including people, things, and systems, will be connected to wireless networks, and an advanced cyber-physical fusion system (CPS) is expected to feedback optimal results to the real world through artificial intelligence (AI) [2]. A CPS is a system concept in which AI creates a replica of the real world in cyberspace (digital twin) and emulates it beyond the constraints of the real world. This concept will provide various values and solutions to social problems. NTT’s Innovative Optical and Wireless Network (IOWN) [3] will accelerate the CPS concept by collecting physical-space information from all devices and generating big data; thus, mobile traffic is growing rapidly toward 6G. The compound annual growth rate of mobile data usage worldwide is reported to 60% [4]. In order to accommodate the explosion in mobile traffic, the use of higher frequencies such as millimeter-wave (mmWave) is key for future wireless communication systems [5]. However, the mmWave bands are characterized by strong direct wave radio propagation, and the mmWave link quality (LQ) is strongly affected by surrounding objects. To ensure stable use of the mmWave bands, we introduce wireless LQ-prediction technology that focuses on the relationship between physical-space information and wireless-link information. NTT Network Innovation Laboratories is researching using physical-space information to promote the evolution to wireless communication systems toward IOWN/6G [6]. 2. Physical-space information and wireless communicationsInformation obtained from cameras/sensors will be usable as physical-space information such as the position, velocity, and status information of wireless devices. Since wireless signals propagate through physical space, wireless LQ is greatly affected by physical space. Therefore, there is a solid relationship between the wireless LQ and physical-space information. NTT Network Innovation Laboratories has focused on the relationship between the wireless LQ and the physical-space information, and developed the wireless LQ-prediction technology [7]. Figure 1 illustrates a wireless LQ-prediction system that predicts future wireless LQ using physical-space information. An environment where pedestrians walk around within the wireless coverage area of a 5G base station is assumed with this system. There are two types of pedestrians, a user equipment (UE) holder and a pedestrian for blocking. The UE holder moves while accessing applications, such as VR/AR, through a 5G base station. The pedestrian also moves around the UE holder. This system gathers the states of the UE holder and pedestrian and wireless LQ as training data. The states as physical-space information, which are the position, direction, and velocity of all the objects such as the UE holder and pedestrian, the throughput of the UE holder as LQ information are obtained from reports via wireless links or cameras/sensors in the communication areas. An LQ-prediction model is trained to output future wireless LQ using the obtained training data based on a machine-learning algorithm.

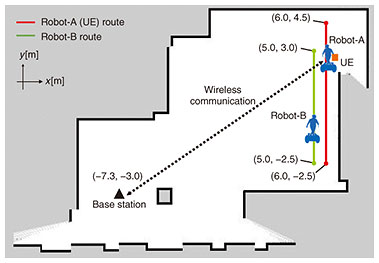

3. 5G throughput-prediction model using physical-space information and experiment environmentLQ prediction based on deep neural networks (DNNs) for mmWave bands is being studied. Physical-space information, such as UE position, camera images, and point-cloud data, have been shown to strongly correlate with mmWave LQ. The received signal-strength-indicator prediction for 60 GHz using depth images from RGB-D cameras in an indoor environment where two pedestrians move between an access point and fixed UE has been investigated [8]. However, a more complicated and practical scene where both the UE and surrounding objects move has not been considered. We constructed and evaluated a DNN-based throughput-prediction model for a 28-GHz 5G channel in a two-pedestrian scenario [9]. We considered a pedestrian scenario in which two people are walking around in an indoor room; one has a UE and communicates via a 5G 28-GHz channel. Figure 2 shows the indoor-experiment map and the different endpoint goals of the two pedestrians. For this scenario, autonomous robots were built to generate training data for the DNN-prediction model. Humanoid Robots-A and B were used as substitutions for the UE holder and pedestrian, respectively. Each consisted of a humanoid mannequin mounted on a mobility robot. Robot-A, which held the UE in a backpack, is shown in Fig. 3. Robot-B for blocking is shown in Fig. 4. Robots-A and B were 1.67 and 1.70 m tall, respectively. These robots were controlled by a robot operating system (ROS) [10]. The robots’ position, velocity, and direction were obtained from the ROS as physical-space information. The robots were equipped with LiDAR (light detection and ranging) and the point clouds of laser-signal reflection points were used to calculate the location and direction. The maximum robot speed was 1.0 m/s. The running routes of Robot-A with the UE and Robot-B are the red and green lines, respectively, in this figure. Robot-B ran between Robot-A and the base station, resulting in a decrease in throughput due to blocking.

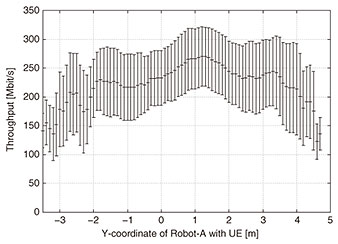

The Iperf [11] software tool was used, and the UE transmitted packets via the User Datagram Protocol to the multi-access edge computing server. Therefore, the measured throughput values were not affected by background Internet traffic. The antenna height of the base station was 2.65 m. The input features of the time series for the past one second on the DNN were ΦT, the past throughput; ΦA, state of Robot-A; ΦAB, states of Robots-A and B; and ΦABT, states of Robots-A and B and past throughput. To benchmark our 5G throughput-prediction model using physical-space information, a conventional prediction model that uses past throughput was prepared. A DNN has three hidden layers: a long short-term memory layer and two fully connected layers spaced with 10% dropout. The activation function for the hidden layers is the rectified linear unit. The DNN is trained to minimize the loss function of the mean squared error. The optimization algorithm is Adam with a learning rate of 0.0005. The output value of our prediction model is one-second-ahead throughput. The throughput and states of Robots-A and B were measured every 100 ms. The resulting dataset contained 1,493,750 samples corresponding to about 41 hours spread over 11 days. These values were normalized to yield a distribution from 0 to 1 or –1 to 1. We used 20% sampling data as test data. The remaining 80% was used as training data (90%), and as a validation data (10%). Since we focus on LQ prediction for detecting the performance drops due to blocking, the upper limit of the measured throughput was set to 200 Mbit/s. Therefore, our prediction model predicts the future throughput with a ceiling of 200 Mbit/s. Figure 5 plots the average and standard deviation of measured throughput versus the y-coordinate of Robot-A. Fluctuations in throughput were observed. When the y-coordinates of Robot-A were around –2.5 and 4.5 m, the throughput fell. These correspond to the endpoint goals of Robot-A shown in Fig. 2, where non-line-of-sight (LOS) occurred due to the rotation of Robot-A.

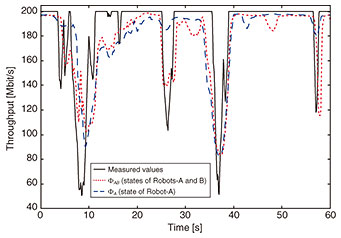

4. Evaluation in an indoor experimentWe conducted a qualitative evaluation of our 5G throughput-prediction model and the measured and predicted values, as plotted in Fig. 6. There were two main factors affecting throughput degradation in our scenario. The first was LOS blockage by Robot-B moving between Robot-A and the base station at around 26 and 58 seconds, as shown in Fig. 6. The observed throughput dropped to about 100 Mbit/s due to the blocking effect of the human body in our environment. This occurred at various locations along Robot-A’s route, and blocking time changed due to the speed and relative directions of Robots-A and B. The second factor was self-blocking by Robot-A, which made a 180 degree turn at each endpoint goal at around 9 and 37 seconds, as shown in Fig. 6. The self-blocking by Robot-A had greater impact on throughput than the LOS blockage by Robot-B as the throughput rapidly dropped below 50 Mbit/s. This is because Robot-A as the obstacle (self-blocking) was closer to the UE than Robot-B, and the 180-degree turn took longer to complete than the blockage by Robot-B.

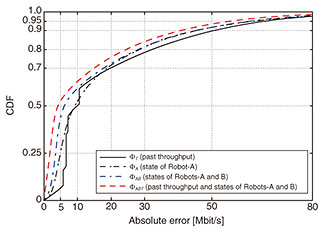

Figure 7 shows the cumulative distribution function (CDF) of the absolute error between the predicted values and observed values. The effectiveness of physical-space information became more prominent as the CDF value fell. The 50th-percentile absolute error value improved by 57.5% using ΦABT, compared with using ΦT, which takes past throughput as the input feature. This result indicates the correlation between the physical-space information and throughput. Additionally, the 70th-percentile absolute error value was less than 20 Mbit/s for all input features, indicating that the absolute errors were concentrated within 20 Mbit/s and correlations were observed between all input features and throughput. Similarly, at the 50th-percentile absolute error value, compared with ΦA, an improvement of 35% was attained by adding the state of Robot-B. This confirms the effectiveness of the states of surrounding objects, such as Robot-B, in throughput prediction.

Figure 7 shows that large prediction errors exceeding 50 Mbit/s occurred. This is because the current input features of past throughput and physical-space information cannot explain the 5G network-driven throughput changes such as link interruption and reconnection. For future work, we plan to consider such throughput changes by adding the 5G network information. 5. ConclusionThis article presented a throughput-prediction technology for 5G services over a 28-GHz channel that uses physical-space information for a two-pedestrian scenario in which both a UE holder and a pedestrian move continuously. To evaluate our throughput-prediction model and collect the learning data required for training the DNN, we developed an actual indoor experimental setup where 5G throughput and physical-space information are automatically measured using autonomous humanoid robots. The throughputs, including the sharp drops due to self-blocking by UE rotation and the blocking by an object moving in front of the UE, were captured. We showed that our model was effective in using surrounding object information as well as UE information for predicting 5G throughput one second ahead. Our model with physical-space information improved prediction accuracy by 57.5% at the 50th-percentile absolute error value compared with a prediction model that uses only the past throughput as the input feature. We will continue this research to develop core technologies toward 6G/IOWN. References

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||