|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

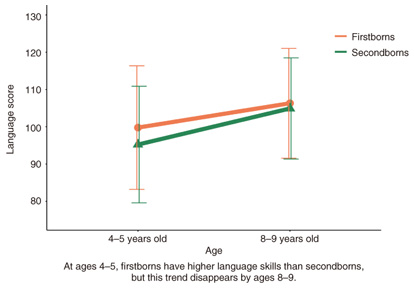

Front-line Researchers Vol. 23, No. 11, pp. 7–13, Nov. 2025. https://doi.org/10.53829/ntr202511fr1  Understanding the Developmental Process of the Human Mind and Undertaking Research to Implement Individually Optimized Educational Support in the FieldAbstractThe Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) reported that in the National Academic Achievement Test conducted in April 2025 for third-grade junior high school students, the correct rate for the essay-style questions in Japanese language, which required students to express their own thoughts in writing, was just 25.6% on average. Some questions had non-response rates of nearly 30%. To understand the essence of a question and to express one’s thoughts requires language skills, which are acquired through linguistic inputs from parents, teachers, and others during infancy and early childhood. Tessei Kobayashi, a senior distinguished researcher at NTT Communication Science Laboratories, has conducted research on child language development. During his research, he proposed and supervised individually optimized picture books, which contribute to educational support for infants and young children. We spoke with him about his thoughts on applying his research findings on “the development of the human mind” as a support tool in the field of child education. Keywords: human mind, child language development, number sense Clarifying the development of the human mind from the perspectives of language, emotions, number sense, and drawing—Could you please tell us about the research you are currently conducting? My research group is conducting research to elucidate the development of the human mind. The aim of this research is threefold: (i) explain the developmental processes related to language, emotions, and other aspects from infancy to childhood; (ii) propose methods for measuring the level of development easily and accurately; and (iii) consider support methods that are individually optimized according to the developmental stage of each child. In my previous interview (December 2022 issue), I discussed the topic of language development. I explained the commercialization of Pitarie, a system that enables users to search for picture books tailored to a child’s interests and developmental stage from the most extensive corpus of Japanese picture books. I also revealed how the amount of linguistic input, in terms of words and letters, that appears in Japanese picture books is related to the language development of young children. After that, I introduced our proposal and commercialization of the Personalized Educational Picture Books, which uses these findings to create individually optimized picture books. Since my last interview, research on child language development has continued. Its scope has been expanded to include the following topics: (i) acquisition of emotion words, (ii) development of friendship, (iii) development of number sense, which forms the basis of arithmetic and mathematical ability; and (iv) development of drawing, which is one of the main activities in early childhood. A recent topic of research is the impact of birth order, specifically being the first or second child, on a child’s vocabulary development. Previous studies conducted in France and Singapore have shown that firstborns have higher language skills than secondborns due to the greater linguistic input from parents in firstborns compared with secondborns. We analyzed data to determine whether this so-called “older sibling effect” also applies in Japan and how this trend changes through childhood (up to elementary-school age). We conducted this research in collaboration with Hamamatsu University School of Medicine. Professor Tsuchiya’s team at the Research Center for Child Mental Development at the university has been conducting a large-scale, birth cohort study on the mental development of over 1200 children in Hamamatsu City since their birth, spanning more than 15 years. Taking advantage of the opportunity to analyze the valuable longitudinal data collected by this cohort study, we focused on language skills (including vocabulary and syntax task scores in intelligence tests) at the ages of 4 to 5. The analysis results revealed that the language skills of secondborns were lower than those of firstborns. This result confirmed that the older sibling effect also occurs among 4- to 5-year-olds in Japan (Fig. 1). The result also indicated no significant difference in the language skills of secondborns in relation to the gender of their older siblings; however, the smaller the age difference between secondborns and their older siblings, the higher the language skills of secondborns tended to be [1]. This trend has also been observed in previous research conducted in France, and it has been suggested that when siblings are close in age, reading picture books to the older child may also serve as effective input for the younger child’s language development.

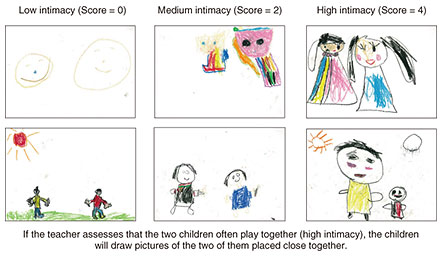

However, when we analyzed the language skills of the same (firstborn and secondborn) children at the ages of 8 to 9, we found no significant difference between the language skills of the children, suggesting that the older sibling effect in language development disappeared during childhood (Fig. 1). We believe that the reason for the disappearance of the older sibling effect is that while 4- to 5-year-olds have more opportunities to interact with caregivers at home, 8- to 9-year-olds (who have started elementary school) have more opportunities to interact with people outside the house such as friends and teachers. This increased interaction with outside people after starting elementary school has a more substantial influence on the secondborn child’s language development. Previous studies did not analyze the older sibling effect during the childhood period; therefore, our findings are the first to report the phenomenon of this effect in language development disappearing in childhood [2]. We are also exploring other topics related to child language development. For example, it is said that if children with hearing problems from birth undergo surgery to fit them with cochlear implants before the age of 2, they will be able to acquire spoken language properly. In collaboration with a team at Shizuoka Prefectural General Hospital, we are currently working on a project to analyze the language development of children with cochlear implants. We are analyzing the vocabulary development of Japanese children raised in institutional care (IC), confirming that IC children aged 0–2 do not exhibit a delay in vocabulary development compared with children raised in biological family care. However, children who have experienced adversity tend to have a slightly more limited vocabulary than those who have not [3]. To clarify the developmental process of reading and the mechanisms underlying dyslexia (i.e., a reading disorder), we are currently conducting extensive surveys on hiragana (a phonetic writing system) reading across multiple regions throughout Japan. Children in some areas exhibit a significant delay in reading hiragana; therefore, we are investigating the possible factors that cause this regional difference. As I mentioned earlier, in collaboration with Hamamatsu University School of Medicine, we are analyzing the language development of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). We are using machine learning techniques to investigate a method for predicting the likelihood of a diagnosis of ASD based on the characteristics of a child’s vocabulary development at 14 months of age [4]. Applying the above evidence, we aim to develop a highly accurate method for assessing language development in infants and young children and theorize the individual differences in language development among children who exhibit diverse developmental patterns. These tools will enable the prediction of development, identify children who are likely to experience difficulties in language development at an earlier stage, and propose optimal learning methods tailored to each individual’s cognitive characteristics. It will thus be possible to provide individually optimized support of language development. —You are researching friendship in combination with drawing, correct? Drawing is a significant activity in early childhood. Everyone loves drawing when they are young. In collaboration with nursery school teachers, we are conducting research on whether children’s drawings express intimacy with others. This research aimed to develop a simple method for measuring the relationships between children on the basis of their daily activities at nursery schools. First, children in a nursery were asked to draw a picture of themselves with another child, who was assigned by teachers in a manner that enabled them to draw children with various levels of intimacy with themselves. The teachers at the nursery were asked to rate how often the children played together on a 5-point scale, and the assigned rating was used to measure the intimacy between two children. A total of 832 children (aged 3 to 6 years old) from 21 nurseries participated in the study, and each child was asked to draw one picture (containing themselves and the other child). The distance between the drawing of themselves and the drawing of the other child was measured and taken as an index of intimacy. Several measurements were taken, and the distances that correlated most strongly with intimacy were twofold: (i) the distance between the closest points of the two figures in the picture, and (ii) the distance between the centers of the two heads of the figures or the centers of the whole figures in the picture. In other words, when children draw themselves and a child they often play with, they position both figures (or faces) closer together, whereas when they draw a child they rarely play with, they position the figures further apart [5] (Fig. 2).

To confirm the above trend, the intimacy between the children was experimentally measured using an alternative approach. In a nursery, the children were asked who they usually play with (up to six children), and their answers were illustrated as their “social network (SN).” In this case, the children assessed their own level of intimacy themselves (self-rating). In contrast, in our previous survey, the teacher assessed the children’s level of intimacy with others (others’ rating). The children were asked to draw two pictures: one of themselves and one of a child who is close to them on the SN, and another of themselves and a child who is distant from them on the SN. The results indicated that the children who were close on the SN tended to draw pictures of the other (intimate) child close to themselves (shorter distance), while the children who were distant on the SN tended to draw pictures of the other child (non-intimate) further away from themselves (longer distance). This self-rating experiment, designed to measure subjective intimacy, thus confirmed that as intimacy increased, the interpersonal distance between the self-drawing and the other-child drawing decreased [6]. These studies have quantitatively demonstrated that intimacy with other children is expressed in the natural activities, such as drawing pictures, of children at nursery school. Clinical psychologists had often inferred a child’s psychological state by asking them to draw a picture. However, we discovered that the drawing reveals not only an individual child’s psychological state but also the characteristics of the child’s relationships with other children. Understanding the interpersonal relationships, isolation, bullying, and other issues that children face at nursery school is a crucial aspect of nursery management. I believe that researching what can be understood through drawing, which is an integral part of a child’s everyday activities, may contribute to addressing these issues. —What kind of research are you conducting on “number sense”? When animals try to catch food in the wild, if one feeding area has abundant food and another has little food, they will go to the one with abundant food. The quantity of food is an essential issue for animals’ survival, so animals need to keep a firm grasp on the amount, and this necessity also holds when animals are searching for a mate. That is to say, heading to places where there are likely to be more of the opposite sex increases the chances of reproduction. Previous research has confirmed that all animal species—ranging from invertebrates (such as bees and ants) to birds (such as pigeons and crows) and mammals (such as rats, monkeys, elephants, and dolphins)—possess the ability to recognize quantities intuitively. That ability is called “number sense.” We humans have inherited this number sense through the process of evolution. As evidence of this evolution, analysis of eye movements has shown that human infants can distinguish between small numerosities (such as 2 and 3) of objects shortly after birth. Even in cases of larger numerosities of objects, such as 4 and 8, infants can still distinguish between them if they are far apart. However, they cannot notice the difference between closer numerosities of objects (such as 6 and 7 or 8 and 9). Like other animals, the number sense of human infants can be described as an “analog representation” that is fuzzy and lacks precision. However, humans have created and developed mathematics, something no other animal in the natural world has ever achieved. It goes without saying that mathematics has contributed to the invention of all artificial objects and the development of natural sciences from the past to the present, and in doing so, it has had a significant impact on the prosperity of human society. Thus, the question is: what was the trigger that elevated the number sense we share with animals to the level of mathematics? When I think about that question, I believe that number sense is inseparable from language. Both animals and human infants have difficulty distinguishing between 6 and 7 objects, and the numbers are represented in an analog way in their brains. However, a language makes it possible to divide analog representations into digital representations, such as “6” and “7”. This shift from analog to digital representation has enabled humans to handle numbers abstractly. From the perspective of human development, the integration of number sense and language begins around the age of two or three, and children can actually count “one, two, three…” from the latter half of age three onwards. Once children learn to count, they can accurately understand not only the numbers 1, 2, and 3 but also larger numbers such as four and beyond. Most children can naturally learn to count in this manner, but some struggle with it. A condition called “dyscalculia,” which manifests as difficulty in learning calculations and arithmetic, has also gained recognition. I intend to pursue further research on the relationship between the development of computational and arithmetic abilities, number sense, and language. The term “number sense” originates from the title of a book called “The Number Sense,” published in 1997. In the book, the author—French cognitive neuroscientist Stanislas Dehaene—reviews animal quantitative cognition, the development of arithmetic and mathematical abilities in infants and children, number-processing mechanisms in the human brain, and historical and cultural anthropological studies of number systems. He thus summarizes why humans were able to develop mathematics. I previously translated the book into Japanese, which was subsequently published in Japan. A second edition incorporating new research developments was published in Europe and the United States. In Japan, it was released in December 2024 by Hayakawa Publishing Corp. under the title “What Is Number Sense? [New Edition]—How the Mind Creates and Manipulates Numbers—(translated by Mariko Hasegawa and Tessei Kobayashi)” [7]. In connection with number sense, in August 2025, a picture book for infants and toddlers titled “A Baby Book of Numbers Without Numbers” (written by Akio Kashiwara and supervised by Tessei Kobayashi) was published by Shufunotomo Co., Ltd. Many picture books dealing with numbers have been published to date, but all are designed to help children learn Arabic numerals (1, 2, 3…). However, according to previous research on number sense, infants do not start with an understanding of Arabic numerals; instead, they enter the world of numbers by using the number sense they share with animals. With that perspective in mind, I wanted to create a picture book that deliberately avoided using Arabic numerals. The book that I supervised [8] is shown in Fig. 3. On the basis of the numbers 1 to 3, which even infants can understand intuitively, the content is designed to familiarize infants with the world of numbers by presenting a series of auditory sounds (“meow,” “meow,” “meow”) via repeated onomatopoeia and a collection of objects (“cat,” “cat,” “cat”) via illustrations. Putting aside my desire to teach children numbers and numeral words from an early age, I hope they will thoroughly enjoy the world of numbers through number sense, which we share with animals.

It is essential to visit the research field and investigate for yourself, as you often gain valuable insights and hints about your research on-site—What do you keep in mind as a researcher? In addition to researching the development of the human mind, I have also studied the behavior of animals, including rats, chimpanzees, and elephants. At that time, it was often difficult to understand what was causing the animals to behave in a certain way solely by examining the data that had been collected, so I supplemented the meaning of the data by observing the animals with my own eyes in the field or in the laboratory. This stance remains the same regarding my current research on children, where I act as a tester while paying attention to the children’s reactions and behaviors at each stage and trying to collect data in the field. While it is possible to conduct analysis using data obtained by others, being in the actual field makes it easier to see what lies behind children’s psychology and behavior. In some cases, you may even find inspiration for your next research topic. When conducting research in the field, various factors, such as the nursery-school environment, children’s behavioral tendencies, and tester’s condition, can cause variation in the research data. If you are in the field, you can sense these factors and make improvements or corrections to your research. For that reason, even as a senior researcher, I make it a point to go into the field and participate in research as a member of a research team. I want to invite experts who support child development to participate in our collaborative research—Do you have a message for people involved in child development and education? The advancement of child-related research fields requires collaboration not only with researchers at universities and research institutions but also with individuals providing specialized support. For example, I’d like to conduct my research in collaboration with many experts, including teachers and library staff at nurseries and daycare centers involved in early childhood education and childcare, local government officials engaged in child-rearing support and therapeutic education, child-welfare workers who support children who have experienced adversity in their childhood, and speech therapists and clinical psychologists who provide medical support to children with delayed language development. Each child shows a different developmental pattern. To provide individual support to these children, we need to mobilize the knowledge and expertise of professionals who work with a diverse range of children. Working hand-in-hand with experts, I am conducting research to provide a comprehensive and detailed examination of child development, uncovering the mechanisms and problems underlying it. I then use this evidence to create valuable tools for on-site work and deploy those tools in the field. I understand that you are busy with your daily work. Still, I encourage you to participate in our joint research from a hands-on perspective, which includes, for example, proposing issues, collecting data, and verifying tools. References

|

|||||||||||||||||